The Lab For Early Social Cognition

What do 3-year ods do when someone around them needs help?

What do 3-year-olds do when someone around them needs help? How will they respond to different “helping scenarios?” In general, how do young children understand and then respond to other people’s goals? Our lab found that children were significantly more likely to help in a scenario with a physical task (i.e picking up a pen someone dropped on the ground) than in a social goal scenario (i.e. helping a researcher get the attention of someone else in the room.) If the child did help in the social goal scenario, they did so less often when the other person had previously indicated that she was busy. Shyer children were less likely to help in the social goal scenario. It is clear that 3-year-old children can be good helpers but are also aware of social context in a group. This research can have implications in developing better practices to help our children socialize: at home, in group settings, and at school. We are incredibly grateful to all the families who generously volunteered their time to participate in this study!

The NeuroCognitive Development Lab

How can brain waves reveal about developmental difference in the memory ability of young children?

Memory is still a mystery to many scientists. Researchers hoped to learn why children’s ability to remember life events with greater detail improves so rapidly in a short amount of time between 3- and 6-years-old. What are the processes in the brain that are evolving and developing? Previous research suggests that memory is not just one ability, but rather the result of multiple processes (called familiarity and recollection). Familiarity allows us to recognize that someone looks familiar (such as when we pass by them in the supermarket), whereas recollection allows us to recollect specific details about that person (e.g., their name, how you know them, when you last saw them, etc…). Research in school-aged children suggests familiarity develops early (by 6-years-old), whereas recollection shows more prolonged development. To look into this more deeply, 76 families with children between the ages of 3- and 6-years-old generously volunteered to come to the Neurocognitive Development Lab on UMD’s campus for two visits. The children played a memory game with researchers who recorded their responses. Our researchers found that children’s brains had different responses to what is familiar vs. what they had to recollect with contextual details. These findings suggest that both familiarity and recollection are developing during this period, which may explain why children’s memory ability change so rapidly during early childhood. Knowing more about how and why memory changes during early childhood is important as it may help us to better detect when memory problems exist and provide information about the best way to intervene when needed.

The Language Development Lab

How can parents help build their infant's vocabulary?

A study from the Language Development lab looked at factors in infants aged 7 months that might enhance their vocabulary as toddlers. The researchers tested infants’ ability to separate individual words from fluent sentences (or to “segment” speech), a skill that normally develops between 6-and 8-months old. They also measured how parents typically spoke to their children. Children who were more adept at segmenting had greater vocabularies at age 2-years. But so, too, did children whose parents repeated words more frequently (separate effects.) These findings suggest that it is beneficial to repeat yourself when speaking to your baby – it will give him or her more chances to learn new words, and result in a larger vocabulary later on!

The Language Development Lab

How does being raised in a billingual home affect children's vocabulary development?

Many children are raised in bilingual homes where they may hear the same adult providing input in multiple languages. Such “code-switching” (CS) could potentially have implications for children’s language learning. Bilingual parents and their 17- to 24-month- old children came to the Language Development Lab for the study. Together, parents and their children played with the toys provided to them. Researchers encouraged them to speak naturally during the session. Parents also filled out surveys to describe the kind of language their child hears on a daily basis. Researchers found that all the parents changed languages at least once during the short play session, which suggests that many infants are likely to hear a substantial portion of code-switching on a regular basis. Importantly, there was no evidence that the input children received had a negative impact of children’s language development. Furthermore, code switching does not appear to be a technique used specifically for teaching, but rather as a way parents get their children’s attention.

Cognition and Development Lab

Do children learn and accept every new thing they hear or see?

Children are constantly exposed to new information about the world- especially in the digital age! It stands to reason that children have to have some level of skepticism about new information in order to learn. Researchers in the Cognition and Development Lab have examined children’s abilities to determine how reliable information is on the basis of several cues available to them. We found that even as young as preschool age, children were able to evaluate "good" claims as more acceptable. Their ratings of acceptance were related to how well they were able to justify their evaluation. These findings add to the body of literature exploring children's ability to evaluate the reliability of information through the course of development and how they access new knowledge. This work is particularly important given that young children are native to a digital age- constantly inundated with new information. Generations to come will have to think critically to navigate masses of information. Ongoing work in our lab also seeks to understand how this skill intersects with other aspects of children’s early social cognition, for instance, their use of social or linguistic information.

The Developmental Social Cognitive Nueroscience Lab

What does the social part of our brain look like in middle childhood?

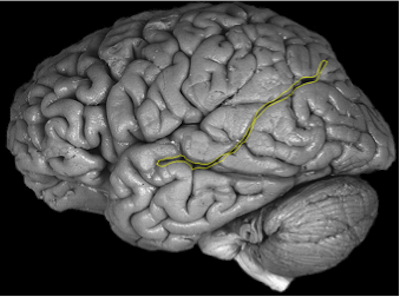

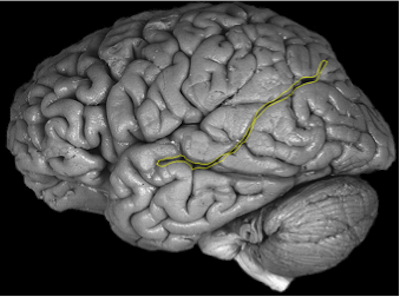

It turns out that from birth, babies prefer watching humans doing human-like things (over watching rocks, trees, chairs, and other non-human things). This preference helps them key in to the social world of humans and teaches them to interact with other people. Previous research has shown that there is a network of brain regions directing these social skills. One such brain region is the “posterior superior temporal sulcus” (say it ten-times fast, or just say “pSTS”), which is outlined in yellow. We know that between the ages of 6- and 12-years-old—about the time kids enter school, start to spend more time with peers, and expand their social circles—that these brain regions get even better and more specialized to learn from and understand the social world. Of course, some children navigate the complex social landscape we refer to as "middle childhood" better than others. Researchers wanted to know if these behavioral differences would be evident in the brain. Local families came to campus to participate and watch videos with human motion while researchers monitored their brain activity. Our findings suggest that the brain response to human motion is closely related to real-world social skills in middle childhood. These findings may have treatment and diagnostic implications for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) or anxiety.

The Developmental Social Cognitive Nueroscience Lab

How does the brain engage in social interaction?

From birth, the human experience is largely defined by our interactions with others, yet scientists are only just beginning to understand how the developing brain functions during social interactions. Furthering this understanding will help uncover what might be different about the brains of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), who have difficulties with social interaction. The Developmental Social Cognitive Neuroscience Lab has developed two novel tasks that allow for real-time social interaction inside the MRI scanner. These tasks are specifically designed for middle childhood (ages 8–12), a dynamic yet understudied period for social and neurocognitive development. Participation in the study involves three visits to the University of Maryland. In the first visit, children individually complete computer-based tasks and surveys that measure how they perceive and think about other people. In the second and third visits, children chat remotely with another child their age while undergoing an MRI scan. During one scan, children share their likes and hobbies and learn whether their chat partners share the same preferences. During the other scan, children learn about their partners’ beliefs, desires, and emotions, then use this information to make predictions about their partners’ choices. Together, these tasks are designed to capture two important aspects of social functioning: social motivation, as reflected by activation of the brain’s reward system during social interaction, and mentalizing (also called “theory of mind”), or the ability to think about the mental states of others.

Project on Children's Language Learning

How do 16-month olds learn new words?

It turns out that 16-month-olds can use language they already know to help them learn new words and new sentence constructions. For instance, if they know what the word pulling means, when a sentence starts with “She’s pulling…” they can predict the next word in the sentence will most likely name a thing being pulled (a chance for learning a new word!) But what happens when their expectations are not met? And what happens when they don't know any of the words in the sentence? This study helps uncover the different strategies children use to learn their language. Researchers did so by comparing children’s ability to learn the novel word “tig,” in the context of two different kinds of sentences: i.e She’s pulling the tig vs. She’s pulling with the tig. We found that the children who knew fewer words at this age were better able to learn what “tig” was naming in each sentence. They have no expectations about what might come after the word “pulling,” but do have an idea about what nouns, verbs, and prepositions are and how they work in a sentence. The children who knew more words at this age learned something different from the video. Based on what they knew about the word “pulling” (that it is usually is followed by a word naming the thing being pulled), they understood “tig” to be the object being pulled, even when “tig” came after “with.” They seemed to be ignoring "with," which did not match their expectations about what kinds of words go with the the verb "pulling." This seeming “regression” in language performance seems to be a typical stage in language development. Eventually all these kids will pick up on the differences in these types of sentences, tackling yet another challenge on their way to language acquisition! We know that between the ages of 6- and 12-years-old—about the time kids enter school, start to spend more time with peers, and expand their social circles—that these brain regions get even better and more specialized to learn from and understand the social world. Of course, some children navigate the complex social landscape we refer to as "middle childhood" better than others. Researchers wanted to know if these behavioral differences would be evident in the brain. Local families came to campus to participate and watch videos with human motion while researchers monitored their brain activity. Our findings suggest that the brain response to human motion is closely related to real-world social skills in middle childhood. These findings may have treatment and diagnostic implications for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) or anxiety.